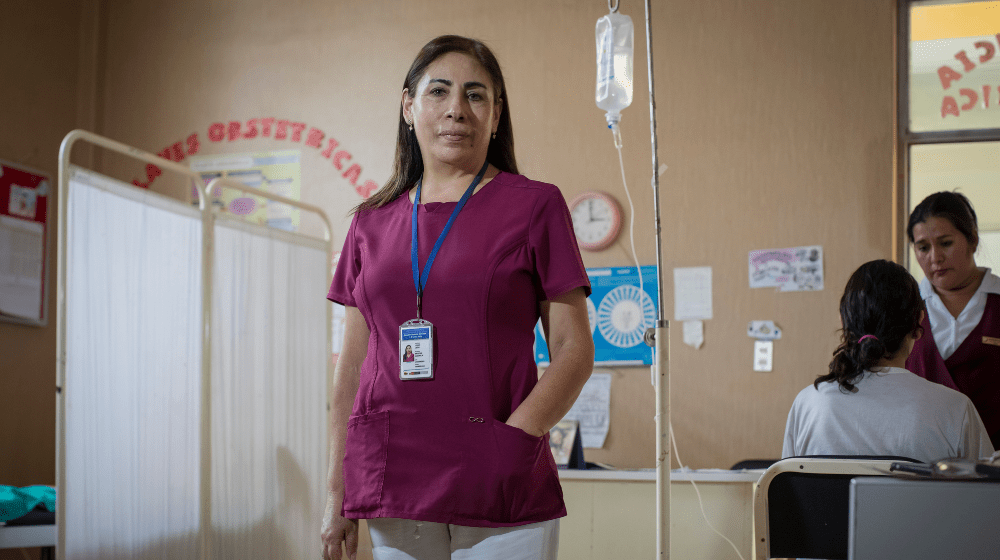

The Santa Julia Health Center, located in the Veintiséis de Octubre district in Piura, was recognized this year by the Judiciary as one of the six best practices nationwide as one of the six best practices nationwide in preventing violence against women. It is an unprecedented model in the country that provides sexual and reproductive health care, psychological support, and legal advice for women affected during the climate crisis, all in a single facility. Bertha Liñán, coordinator of the obstetric service, explains how care was strengthened this year with the participation of brigade members in alliance with the “Saving Lives” project of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

It rained and thundered in Piura, but the Santa Julia Health Center never closed its doors. Bertha Liñán (55), coordinator of the obstetric sexual and reproductive health service, recalls that the priority was to keep the service open, despite the fact that flooding caused a large part of the city’s services to collapse. The streets were flooded. Uncertainty hung in the air. Floodwaters prevented regular transportation. Thousands of women, many of them pregnant women from the poorest areas of the Veintiséis de Octubre district, had been cut off from the only medical facility close enough to attend to any emergency.

“Everyone said the world would end because in Piura it’s not normal to have thunder, lightning, and bolts, let alone a carpet of crickets. It was like a nightmare,” recalls Bertha. Nurses, technicians, and midwives were late, but they kept coming. Shifts were altered. Solidarity stayed afloat. “The goal was to not stop working. The goal, as far as possible, was to continue providing care,” she says, although the real concern was for the patients. The questions were many: how would they be getting through? How would they get to their appointments? How could they receive health services amidst such chaos?

“The problem was patient access to the facility. They couldn’t come as they had ponds in their homes or the streets. And we couldn’t go to them due to the heavy rains. It was a frustrating situation,” says Bertha. The few pregnant women who had managed to avoid the rains and floods were faced with an even more chaotic scenario. Some delivery rooms were flooded with water. They had to go to other health centers, but the collapse was widespread. “Many were sent from one facility to another because we were unprepared. Some patients spent an entire night walking around, begging for care. It was really heartbreaking,” she recalls.

With more than twenty-five years as a midwife at the Santa Julia Health Center, Bertha knows very well the living conditions of this population of 29,000 people directly and 159,000 indirectly in the surrounding areas. Girls, adolescents, women, and mothers are often exposed to misinformation, poverty, and danger. “In this type of emergency, women are always affected in a household. Women with fewer resources who lost their homes had to live in overcrowded conditions, and that resulted in more gender-based violence and more teenage pregnancies,” she explains.

The isolation of all these women was a ticking time bomb. The lack of access to contraceptive methods, information, and medical and psychological support called for another form of intervention. Since May, the distance imposed by the climate crisis began to shrink. The participation of brigades from the “Saving Lives” project, promoted by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) as part of the joint response of the United Nations System with funding from the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), enabled trained midwives to provide essential sexual and reproductive health services to pregnant women and adequate counseling to adolescents and young women of childbearing age. “The brigade members began to go tirelessly door to door to provide sexual and reproductive health counseling and to spot pregnant women. And they haven’t given up,” says Bertha.

Although this task is usually carried out by the State, resources are sometimes scarce, especially during a climate crisis such as the one that affected more than 400,000 people in the departments of Piura, Tumbes, and Lambayeque. “The brigade members have helped us increase our staff numbers to be able to do a good job, reaching the farthest places where we couldn’t go before,” explains Bertha. The indicators improved immediately. More and more women were able to learn about the sexual and reproductive health services that the Santa Julia Health Center offered: family planning counseling, prenatal check-ups, and 24-hour deliveries, but above all, a safe space where they could get all the necessary support in the event of gender-based violence.

Santa Julia Health Center has had a Women’s Emergency Center (CEM) within its premises for six years. In this space, coordinated with the Aurora National Program of the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations and the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, and the only one of its kind in Peru, any woman who arrives for any health service can be referred to psychological and legal assistance in case she is a victim of violence in any of its forms. Care includes activation of the pink key with the delivery of a medication kit for the sexually assaulted patient within 72 hours.

“We are a model, you could say. A coordinated center that, thanks to the brigade members, more women know it exists, which helps to report these cases more quickly,” says Bertha.

In a city as sexist as Piura, where it can be normalized for a 13-year-old girl to get pregnant, according to Bertha, the existence of the CEM within the Santa Julia Health Center has become even more relevant in times of climate emergency. “Especially because problems of sexual and reproductive health and gender-based violence have worsened,” she says. In the Veintiséis de Octubre district in Piura alone, over 65% of the population, mostly women, are victims of psychological and sexual violence, according to data from the Aurora National Program.

For Manuel Girón, chief physician of the Santa Julia Health Center and general coordinator of the Integrated Health Network in this district of Piura, this innovative form of joint intervention is a model that should be replicated. “That is the advantage we have,” he says, eyeing the next step: strengthening the Comprehensive Care Center. The objective of this center is to increase access to social, legal, and health services for women and girls experiencing violence in the district.

Recognition soon followed. Last June, the Judiciary awarded Santa Julia’s experience as one of the six best initiatives in the “First National Contest for the Recognition of Good Practices developed by justice operators in preventing violence against women”.

According to Girón, none of this could have been achieved without the joint efforts of various actors. One of them is UNFPA, which helped with the implementation of the Comprehensive Care Center in 2017 (following that year’s “El Niño” phenomenon), the validation of some intervention protocols, the training of medical staff, the hiring of gynecologists and the deployment of support brigades to reach the most vulnerable areas. “It has been our key ally,” Girón remarks. The results are obvious: earlier diagnosis of pregnant women in the peripheral neighborhoods, coverage of more than 1,700 families in terms of family planning, and a 20% reduction in teenage pregnancy compared to 2022. “For us, it is crucial that this agreement is maintained and that UNFPA can continue to provide this support,” says the physician.

Over the last few months, Bertha has witnessed all these changes. Swimming against the tide is much more than a metaphor. Faith in collaborative work has made it possible. “I couldn’t be prouder of my team. Santa Julia Health Center is my second home,” she says.